Is It Safe Enough? An IPA Study of How Couple Therapists Make Sense of Their Decision to Either Stop or Continue with Couple Therapy When Violence Becomes the Issue

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“At times, I get the same sensation as if I’m sitting in a packed conference hall with 5000 people. It’s that moment when you raise your hand to speak and that unmistakable feeling, that’s what I sense sometimes. It’s a profound discomfort. You feel it in your stomach, almost like a sensation of weightlessness, as just before you’re taking a leap. Because that’s what it feels like sometimes in our line of work. You’re taking a leap, making a choice. Because that’s the way it is. Sometimes you have to make a choice that you’re acutely aware that this may have consequences. That’s just the nature of our job”.(Stig, a participant therapist from focus group 4)

“a crucial practice in psychotherapy, whereby explanations for experience are brought together with an evidence base for practice within an ethical framework of conduct. This guides and directs action for all participants within an iterative process of feedback and action. Formulation is emancipatory in intent, and provides accountability for practice.”

2. Methods

2.1. The Research Context

2.2. Design and Method

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Participants and Recruitment

2.5. Analysis of the Focus Group Data

- Step 1: Identifying the researcher’s orientation and potential bias

- Step 2: Immersion in the data and exploratory noting

- Step 3: Multiple readings with different emphases

- Step 4: Identifying, highlighting, and clustering quotes

- Step 5: Constructing experiential statements

- Step 6: Searching for connections across experiential statements in the particular focus group

- Step 7: Searching for connections across group experiential statements across the focus groups

- Step 8: Checking individual transcripts to ensure nothing missed

3. Results

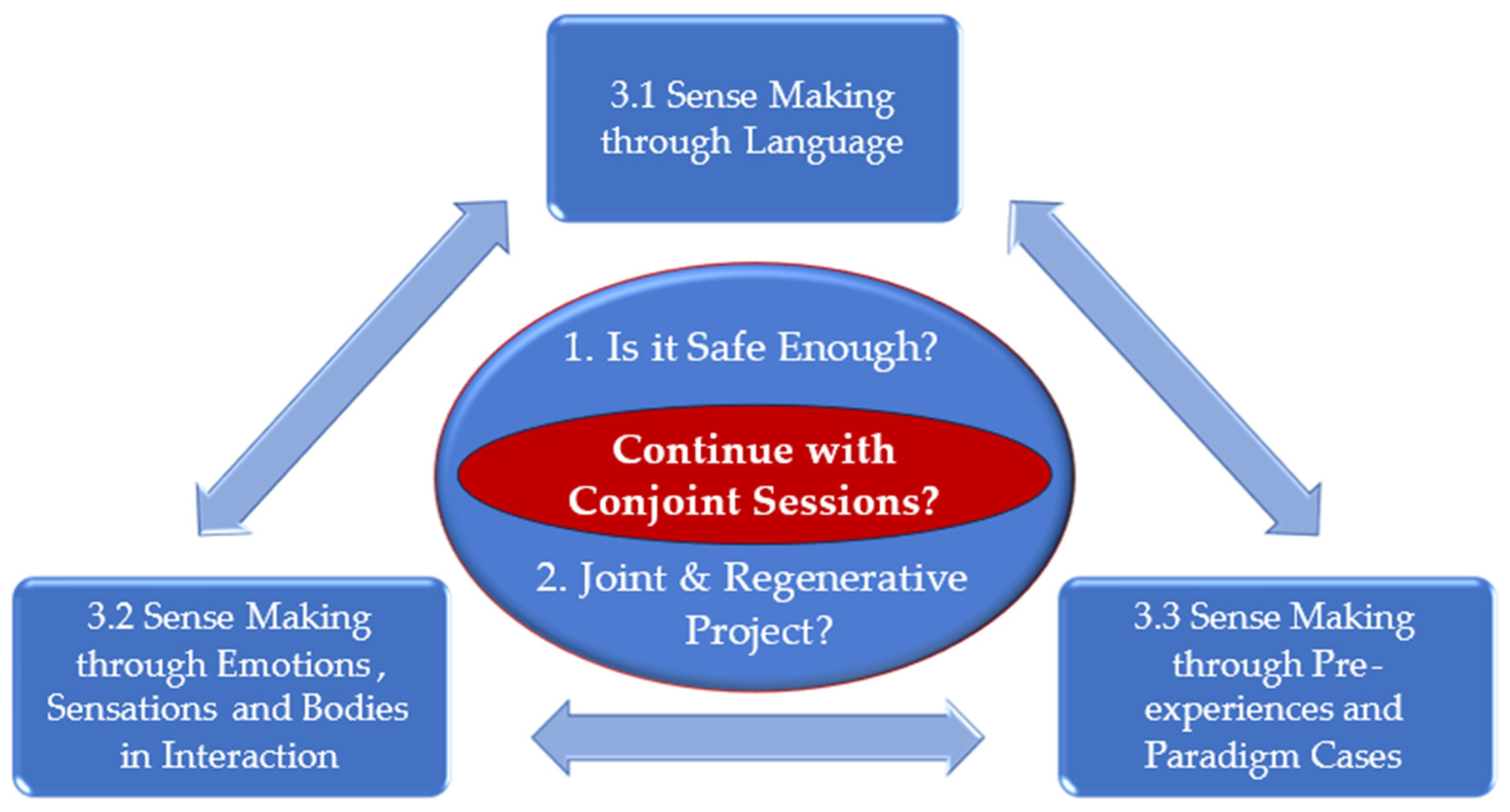

3.1. Group Experiential Theme 1: Is It Safe Enough?

“I think it’s an uncertainty that I feel, and sometimes I can get anxious about maintaining the same pattern that’s already there… It feels scary to be part of something that maybe makes it even harder for the couple.”

“Is this safe enough? Maybe, okay yes, this is safe enough, and we have a common goal. However, then, (pause) I think, it may not be after all. Down the line, sort of, that it could change. Um, or the violence, in a sense, can continue in hiding… It’s sort of something you have to, or continue to be a thought then, you must be open to it.”

3.1.1. Forms and Frequency of Violence

“If there is severe aggravated violence, repeatedly over time, then we would be much more…, so we probably would not start couple therapy.”

“How has it been in the past, and what do they think about the future, for each one of them? That can inform different perspectives on how long this has been going on? How has the development been? Has it gotten worse? Has it been static? Has it gotten better? What do you think it will look like in five years? I think these questions often help both me and them to say something about, what shall we do now?”

3.1.2. Patterns of Power and Coercive Control

“If you subject someone else to a regime, that becomes very, very, if people start doing things they don’t want to do, or they don’t do things they want to do. And that, in addition, is systematised over time with a certain intensity. I think there’s quite a lot of that.”

“If there is so much fear or it is too unsafe, and the imbalance is so great, I have mostly split them and talked to them individually, then you as a therapist start to think of other ways to go than conjoint couple therapy.”

3.1.3. The Degree of Severity, Fear and Latent Violence

“I have a couple now where there was a violent incident 13 years ago, a very severe incident of violence. And, and it’s a very illustrative example then, where, of how serious violence can be then. Because it still controls their lives really…Um, and it has been a big part of their family life for all these years until now.”

“I have a new case like that, where it’s very much latent violence. He says there haven’t been many incidents in quite a while. And she agrees with that, but it is the latent violence that she struggles with, how she navigates to avoid new episodes, and that she’s afraid of it. She walks with that fear within, despite there aren’t many new and concrete episodes.”

“In a way, it is a prerequisite to creating a sense of safety that they will be able to talk about something that difficult.”

3.1.4. The Children’s Situation

“We have these cases and where we think that here there are quite different weighted power relations in the relationship, here there is a high degree of psychological violence, here there are some children who are quite harmed by it, and then we think: ‘but I can’t do anything here’. Here it is too fragile, here it is too depleted, here they are too worn-out. Then we send a report of concern (CPS), and then we get that dismissal back, where you then think, what do we do now? So, then there are some people who don’t get help, and here are some kids who are suffering. And I’ve assessed that I can’t do anything here because it’s too depleted, too severe, and impossible for the Family Counselling Services to do good enough work here in this case. I think there is someone who, first and foremost, must go in and inquire how the heck those kids are doing! And then it gets dropped!”

3.1.5. Substance Abuse and Trauma

“Lots of abuse, and you name it. So, so it’s a question of whether she’ll ever come out of going into old feelings all the time.”

“In some of these cases, substance abuse is also involved, and it is also a complex factor that has to do with safety and insecurity. Sometimes it is the person who is exposed, and sometimes it is the person who commits the violence that has a substance abuse problem.”

3.1.6. Acknowledgement of the Violence

“There is no acknowledgement of the violence, like the guy we worked with, and then we don’t go into it, it becomes like a criterion. We have to see that recognition.”

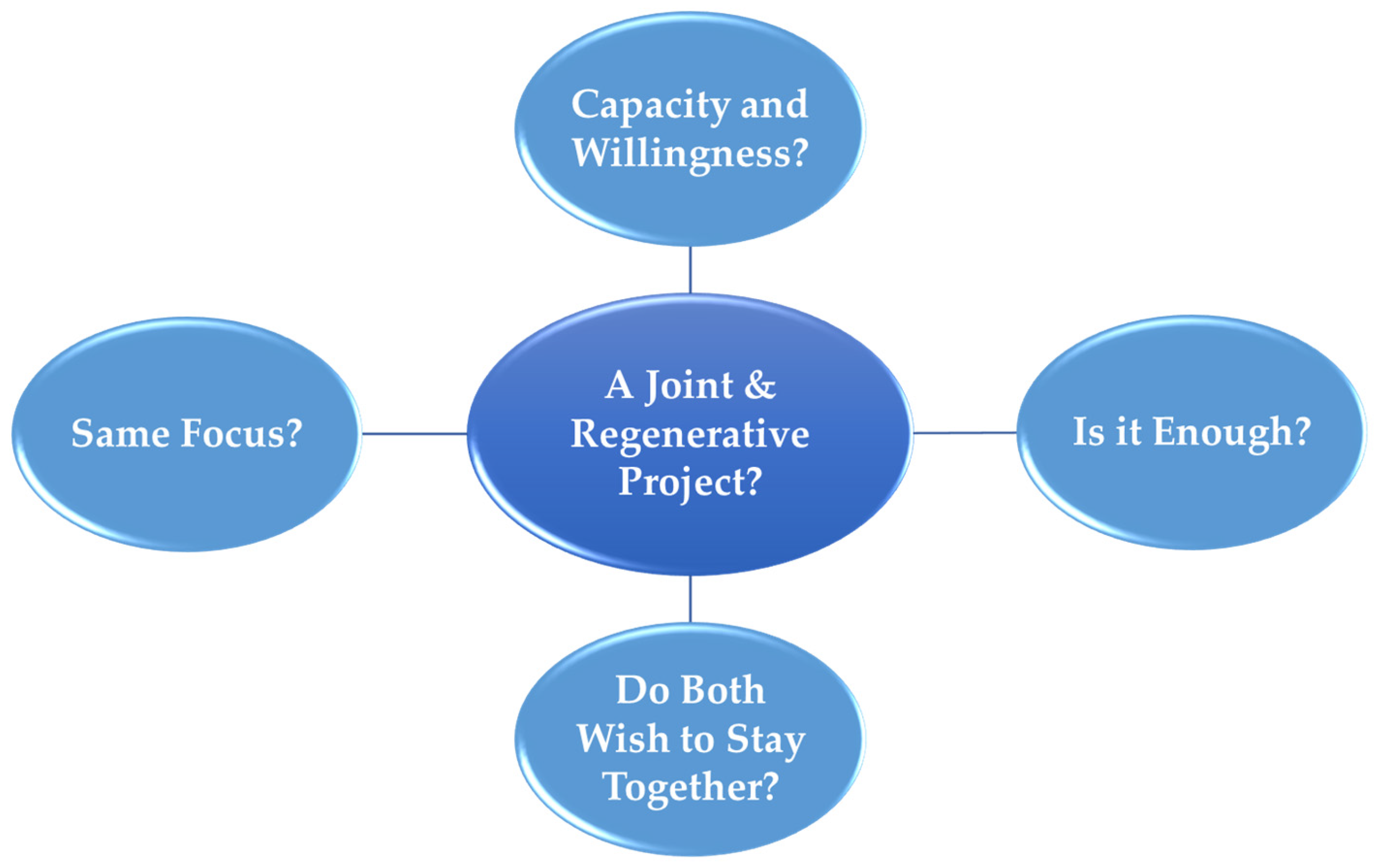

3.2. Group Experiential Theme 2: Do We Have a Joint and Regenerative Project?

“In my experience, it is, in a way, not how severe the violence is that decides. I’ve had quite a few cases and have now, where there’s been a stranglehold, physically damaging violence, and visits to the emergency room. So that’s not what necessarily excludes me from thinking that we can do something together. It is the extent to which both parties are willing to take responsibility, look at their contributions and are, in a way, prepared to work seriously and prioritise from session to session. So it’s like, yes, it’s people’s motivation, ability, and willingness to look at what they’re doing, which is important in the first place. But then there’s something about when we experience that it doesn’t have the progression we hope for. In terms of frightening events coming to an end, um, what are we doing then?”

3.2.1. Do Both Partners Wish to Stay Together?

“In the first session, he’s very keen for it to be a couple therapy, and find back to each other or repair and strengthen the relationship, while she leans more out of the relationship.”

“I think there are a striking number of cases in that area of clarification. So it’s nice then, I think, that those people get the opportunity to reflect with themselves and their partner on what they shall do now. Before we move on, so they don’t rush into either strengthening or breaking up the relationship.”

“Yes, and many of those who come to us in a clarification phase, often one of them have decided in advance that they are not going to continue with this, but need a safe process on it.”

3.2.2. Same Focus?

“It’s a challenge that sometimes I think, oh my God, you have to break up, long before the people in question think so, and then it’s not certain that I am a very good therapist, if I have a different solution in my head, than they do themselves. So it’s tough, like that tipping point, how am I going to be able to follow somehow closely enough on the client’s process then?”

3.2.3. Capacity and Willingness to go to therapy?

“Thank goodness we are able to change behaviour, we humans, but that requires an enormous presence and capacity that is quite fierce.”

“If you’re satisfied in your “current life” or have too much control of the situation. Either way, it’s difficult, through talking, getting them to think: oh, now I really have to pull myself together because this isn’t good for us. That’s not easy.”

3.2.4. Is It Enough?

“And then there’s always that consideration of whether there’s better services elsewhere.”

“And I said that to the couple. That I think this is not fair to you. No, because it’s too insufficient help at this point, so how can we think about the situation then?”

“It’s been two weeks since we last saw each other, right? Has it been a particularly frightening or particularly scary episode since the last time? How have you experienced it? So, so like that…, I try to get to the worst thing that’s happened since the last time, and then we unpack it behaviourally.”

“So it’s both about, does it look like they’re starting to think differently about themselves and their situation? Does it look like this change in perception transfers into the action they actually do? That’s on the one hand, but also to what extent is there in a way any change in meaningful understanding of what is happening to them, and what they themselves contribute, are they helping or maintaining the situation?”

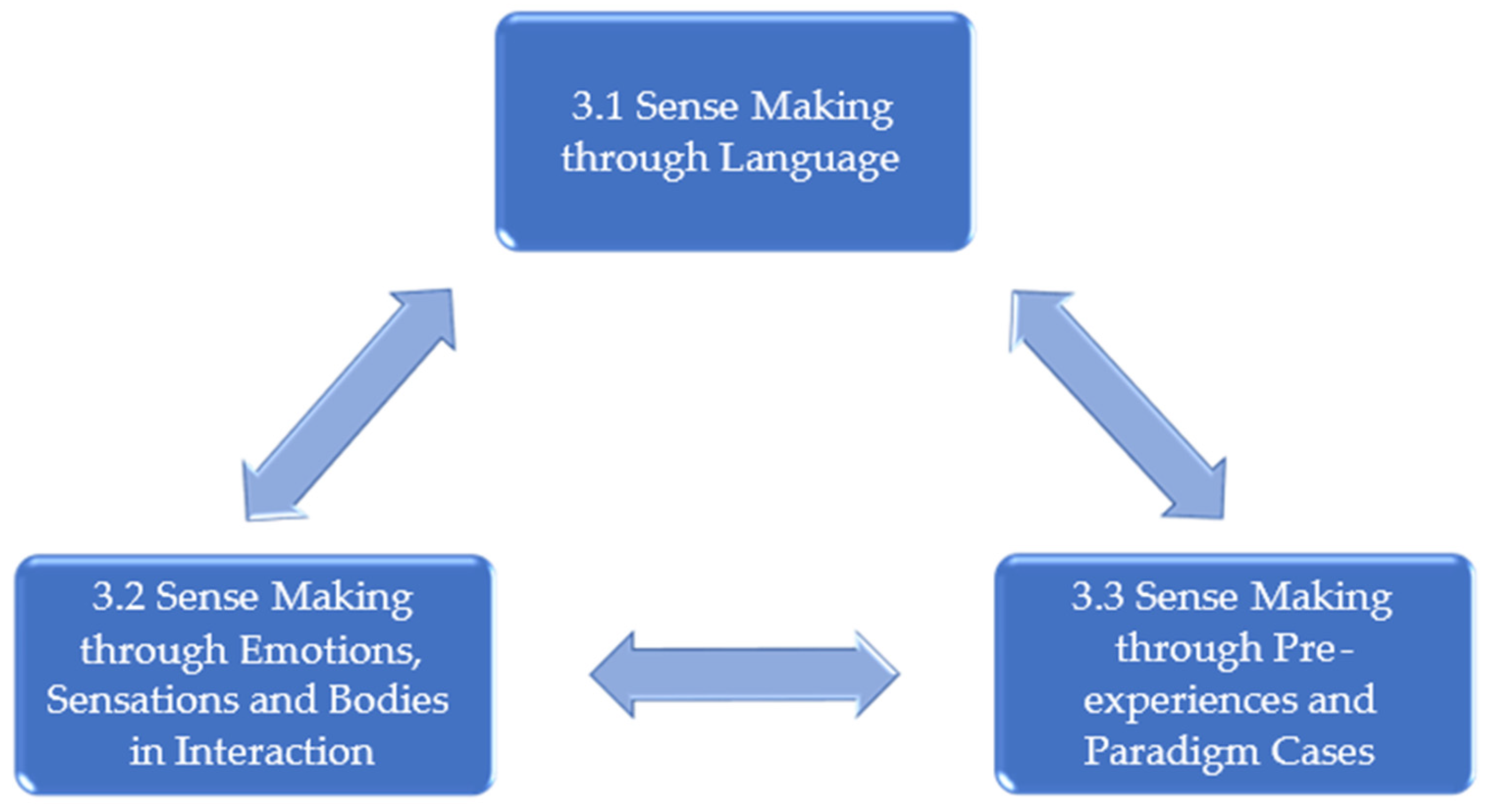

3.3. Group Experiential Theme 3: Three Key Sources for Sense Making

3.3.1. Sense Making through Language

“I thematise equality and power and coercive control in the relationship. How it feels, um, and that’s a way for me to check out, my concern then. If I get, get more worried, after checking out that topic, um, in relation to, who makes decisions, relative to, it could be about finances. It could be about, about, that with respect to each other: Um, and that’s a way of checking out, was my hunch right?”

“To go further into what, what else is there in that relationship of different power aspects then, i.e., what kind of powerlessness is it that who experiences, in what situations, and what kind of power positions exist, what does that do to the dynamics of the relationship and communication then?”

3.3.2. Sense Making through Emotions, Sensations and Bodies in Interaction

“That dynamic, coming in from the waiting room, as they walk into the office, how they sit down, how they talk, don’t talk to each other, also how they, too, how they react when I say that I want to have individual conversations with them, that is, all these responses then. Both how they manoeuvre in relation to each other and in relation to me, it gives a lot.”

“If it’s very, if there’s a feeling or atmosphere so intense as to seem almost tangible in the room, one that’s very tense, trembling, one of them don’t make eye contact, and the other is very, what should I say, one is very eager to speak, and lays out the situation. Then I can feel the discomfort and distress that, here’s something, um, and it kind of stops the possibility to go as far into the landscape as I might have.”

“I don’t sit with that sensation without doing something then, so I’m kind of like, I’m always doing something when I get a hunch like that, or, if talked about, it’s rare, so I try to be transparent then, so, so I’m probably transparent when I’m working with couples… But that has to be my assessment of, what can I say, or how worried am I that something wrong will happen then? Yes, if I am sufficiently afraid of it, I will contact my colleague or manager. Um, or, or am I sufficient, then I will, in a way, wait to talk about these things and check it more out in individual conversations.”

3.3.3. Sense Making through Pre-Experiences and Paradigm Cases

“I’ve probably been scared myself, when I’ve discovered afterwards how ugly it has been and how close to death one of the parties has been, so it’s probably made me even more, maybe sensitive, but very alert to asking what kind of violence are we talking about? How far does it go? How hard do you hit? What did you use? Right? How serious is this in terms of survival? Because I’ve become, maybe I’ve been secondarily traumatised (laughs), but I’ve been a little intimidated a few times by how close it’s been in terms of going awfully wrong.”

“I had a couple where I felt very strongly there was something wrong. He was quite big, and she was small, and she was very tense. I had a couple of conversations with them, and then lost them. And I thought, there was probably violence there, I’ve thought subsequently. And it’s comes to me, many times since then. I have that picture with me. They slipped through my hands. At that time, I didn’t have enough training and was too new, but that picture I have, of that tension and anxiousness. So I can recognise it. Right, I see, very. It’s stuck like such a powerful memory. When I see it, in a way, I recognise that tension (in new cases)… It affects me, now I need to be more sharpened.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Therapeutic Practice

4.2. Reflections on the Limitations and Strengths of the Study and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Visser, M.; Van Lawick, J.; Stith, S.M.; Spencer, C. Violence in families: Systemic practice and research. In Systemic Research in Individual, Couple, and Family Therapy and Counseling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Heimer, G.; Lucas, S. Violence and Health in Sweden: A National Prevalence Study on Exposure to Violence among Women and Men and Its Association to Health; National Centre for Knowledge on Men’s Violence Against Women (NCK): Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haaland, T.; Clausen, S.-E.; Schei, B. Vold i Parforhold-Ulike Perspektiver: Resultater fra den Første Landsdekkende Undersøkelsen i Norge; Norsk Institutt for By- og regionforskning: Oslo, Norway, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.G.; Basile, K.C.; Gilbert, L.K.; Merrick, M.T.; Patel, N.; Walling, M.; Jain, A. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 State Report; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Thoresen, S.; Hjemdal, O.K. Vold og Voldtekt i Norge. En Nasjonal Forekomststudie Av Vold I Et Livsløpsperspektiv Rapport; Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress A/S: Oslo, Norway, 2014; pp. 1–179. Available online: https://nkvts.no/content/uploads/2015/11/vold_og_voldtekt_i_norge.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Jose, A.; O’Leary, K.D. Prevalence of partner aggression in representative and clinic samples. In Psychological and Physical Aggression in Couples: Causes and Interventions; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, L.E.; Doss, B.D.; Wheeler, J.; Christensen, A. Relationship violence among couples seeking therapy: Common couple violence or battering? J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2007, 33, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, S.; Følling, L.; Gulbrandsen, O. Registrering av fysisk vold i familier: En undersøkelse foretatt ved familierådgivningskontorene i Oslo. Fokus På Fam. 1983, 11, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Flåm, A.M.; Handegård, B.H. Where is the child in family therapy service after family violence? A study from the Norwegian family protection service. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2015, 37, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatnar, S.K.B. Familievold og familievern. Presentasjon og drøfting av en kartleggingsundersøkelse ved Familievernkontorene i Norge. Fokus På Fam. 2000, 28, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Stith, S.M.; Rosen, K.H.; McCollum, E.E. Effectiveness of couples treatment for spouse abuse. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2003, 29, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stith, S.M.; McCollum, E.E.; Amanor-Boadu, Y.; Smith, D. Systemic perspectives on intimate partner violence treatment. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakurt, G.; Whiting, K.; van Esch, C.; Bolen, S.D.; Calabrese, J.R. Couples Therapy for Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2016, 42, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetere, A.; Cooper, J. Working systemically with family violence: Risk, responsibility and collaboration. J. Fam. Ther. 2001, 23, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Vetere, A. Domestic Violence and Family Safety: A Systemic Approach to Working with Violence in Families; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, A.J.; Bartholomew, K.; Trinke, S.J.; Kwong, M.J. When loving means hurting: An exploration of attachment and intimate abuse in a community sample. J. Fam. Violence 2005, 20, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slootmaeckers, J.; Migerode, L. Fighting for connection: Patterns of intimate partner violence. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2018, 17, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slootmaeckers, J.; Migerode, L. EFT and Intimate Partner Violence: A Roadmap to De-escalating Violent Patterns. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetere, A. Working Systemically with Family Violence and Attachment Dilemmas. In Attachment Narrative Therapy: Applications and Developments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, J.; Johnson, R.; Koziol-McLain, J.; Lowenstein, S.R. Domestic violence against women. Incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA 1995, 273, 1763–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.G.; Dayle Jones, K. Continuum of conflict and control: A conceptualization of intimate partner violence typologies. Fam. J. 2010, 18, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokkedahl, S.B.; Elklit, A. Undersøgelse af Indbyrdes Vold; Videnscenter for Psykotraumatologi, Syddansk Universitet: Odense, Denmark, 2018; pp. 1–101. Available online: https://bm.dk/media/17153/undersgelse_af_indbyrdes_vold_16-01-2018_endelig.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Johnson, M.P.; Leone, J.M.; Xu, Y. Intimate terrorism and situational couple violence in general surveys: Ex-spouses required. Violence Against Women 2014, 20, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stith, S.M.; Spencer, C. Commentary: 25 Years After Johnson’s Typology of Intimate Partner Violence the Impact of Johnson’s Typology on Clinical Work. J. Fam. Violence 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.B.; Johnson, M.P. Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: Research update and implications for interventions. Fam. Court Rev. 2008, 46, 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. A Typology of Domestic Violence: Intimate Terrorism, Violent Resistance, and Situational Couple Violence; Northeastern University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.P. A personal social history of a typology of intimate partner violence. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2017, 9, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R. Typologies of intimate violence and assessment: Making the distinction. Fam. Ther. Mag. 2007, 6, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Stuart, G.L. Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Patriarchal Terrorism and Common Couple Violence: Two Forms of Violence against Women. J. Marriage Fam. 1995, 57, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.C.; Lasser, J.; Simpson, G.L. Legal and ethical issues in couple therapy. In Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy, 4th ed.; Gurman, A.S., Ed.; Guilford Press: Guilford, UK, 2008; pp. 698–717. [Google Scholar]

- Aldarondo, E.; Straus, M.A. Screening for physical violence in couple therapy: Methodological, practical, and ethical considerations. Fam. Process 1994, 33, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.D. Ethical considerations for clinicians treating victims and perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Ethics Behav. 2017, 27, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.; Bogo, M. The different faces of intimate violence: Implications for assessment and treatment. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2002, 28, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetere, A. Commentary-The role of formulation in psychotherapy practice. J. Fam. Ther. 2006, 28, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L.; Dallos, R. Formulation in Psychology and Psychotherapy: Making Sense of People’s Problems; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht, R.L.; Dimidjian, S.; George, W.H.; Berns, S.B. Domestic violence assessment procedures among couple therapists. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2009, 35, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, T.L.; Pritchard, M.M.; Reeves, K.A.; Hilterman, E. Risk assessment in intimate partner violence: A systematic review of contemporary approaches. Partn. Abus. 2013, 4, 76–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Norway. Family Counselling Service. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/sosiale-forhold-og-kriminalitet/barne-og-familievern/statistikk/familievern (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Barne- likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet. Tildelingsbrev til Barne-, Ungdoms- og Familiedirektoratet 2013; Barne- likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2013; pp. 1–49. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/e3c03f39789d433a9ade95467740b6ab/tildelingsbrev_til_barne-_ungdoms-_og_familiedirektoratet_2013.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet. Prop. 12 S (2016–2017). Opptrappingsplan mot Vold og Overgrep (2017–2021); Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2016; pp. 1–101. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/f53d8d6717d84613b9f0fc87deab516f/no/pdfs/prp201620170012000dddpdfs.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Barne- ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet. Dimensjonering og Organisering av Familieverntjenestene—En Evaluering; Barne- ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet: Oslo, Norway, 2014; pp. 1–57. Available online: https://bibliotek.bufdir.no/BUF/101/Dimensjonering_av_familievernet_evaluering.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. Meld. St. 15 (2012–2013) Forebygging og Bekjempelse av Vold i Nære Relasjoner; Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2013; pp. 1–137. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/1cea841363e2436b8eb91aa6b3b2d48e/no/pdfs/stm201220130015000dddpdfs.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. Et Liv uten Vold. Handlingsplan mot Vold i Nære Relasjoner 2014–2017; Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2014; pp. 1–30. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/97cdeb59ffd44a9f820d5992d0fab9d5/hplan-2014-2017_et-liv-uten-vold.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Royal Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Action Plan against Domestic Violence 2012; Royal Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security: Oslo, Norway, 2012; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/a48f0a1fb807453cb4469373342374c5/actionplan_domesticviolence.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- McLeod, J. Qualitative Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.E.; Slark, J.; Gott, M. Unlocking intuition and expertise: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis to explore clinical decision making. J. Res. Nurs. 2019, 24, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, S.; Ruel, B.; Seamark, C.; Seamark, D. Experiences of patients requiring strong opioid drugs for chronic non-cancer pain: A patient-initiated study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2007, 57, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, E.A.; Quayle, E. The Impact of Iatrogenically Acquired Hepatitis C Infection on the Well-being and Relationships of a Group of Irish Women. J. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, P.; Knussen, C.; Duncan, B. Re-appraising HIV testing among Scottish gay men: The impact of new HIV treatments. J. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins, L.; Eatough, V. Reflecting on the use of IPA with focus groups: Pitfalls and potentials. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2010, 7, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.; Larkin, M.; De Visser, R.; Fadden, G. Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2010, 7, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Nizza, I.E. Essentials of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, K.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Exploring lived experience. Psychologist 2005, 18, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Love, B.; Vetere, A.; Davis, P. Should Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) be Used With Focus Groups? Navigating the Bumpy Road of “Iterative Loops,” Idiographic Journeys, and “Phenomenological Bridges”. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallos, R.; Vetere, A. Researching Psychotherapy and Counselling; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. Generative metaphor: A perspective on problem-setting in social policy. Metaphor Thought 1993, 2, 137–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.G. EPZ Truth and Method; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. The Cultural Politics of Emotion; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. The Compass of Mourning. Available online: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n20/judith-butler/the-compass-of-mourning (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Vetere, A.; Sheehan, J. Supervision of Family Therapy and Systemic Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S.; Thompson, N. The Critically Reflective Practitioner; Macmillan Education UK: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tuval-Mashiach, R. Raising the curtain: The importance of transparency in qualitative research. Qual. Psychol. 2017, 4, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Demographics | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 6 |

| Male | 6 |

| Age | |

| 41–50 | 3 |

| 51–60 | 8 |

| 61– | 1 |

| Years in the NFCS | |

| 0–5 | 2 |

| 6–10 | 5 |

| 11–20 | 3 |

| 20– | 2 |

| Name of the Sub-Themes | FG 1 | FG 2 | FG 3 | FG 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forms and frequency of violence | X | X | X | X |

| Power and coercive control | X | X | X | X |

| The degree of severity, fear and latent violence | X | X | X | X |

| The children’s situation | X | X | X | X |

| Substance abuse and trauma | X | X | X | X |

| Acknowledgement of the violence | X | X | X | X |

| Name of the Sub-Themes | FG1 | FG 2 | FG 3 | FG 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do both partners wish to stay together? | X | X | X | |

| Same focus? | X | X | X | X |

| Capacity and willingness to go to therapy | X | X | X | |

| Is it enough? | X | X | X | X |

| Name of the Sub-Themes | FG 1 | FG 2 | FG 3 | FG 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense Making through Language | X | X | X | X |

| Sense Making through Emotions, Sensations and Bodies in Interaction | X | X | X | X |

| Sense Making through Pre-experiences and Paradigm Cases | X | X | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Snellingen, J.F.; Carlin, P.E.; Vetere, A. Is It Safe Enough? An IPA Study of How Couple Therapists Make Sense of Their Decision to Either Stop or Continue with Couple Therapy When Violence Becomes the Issue. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010037

Snellingen JF, Carlin PE, Vetere A. Is It Safe Enough? An IPA Study of How Couple Therapists Make Sense of Their Decision to Either Stop or Continue with Couple Therapy When Violence Becomes the Issue. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSnellingen, Jan Frode, Pål Erik Carlin, and Arlene Vetere. 2024. "Is It Safe Enough? An IPA Study of How Couple Therapists Make Sense of Their Decision to Either Stop or Continue with Couple Therapy When Violence Becomes the Issue" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010037

APA StyleSnellingen, J. F., Carlin, P. E., & Vetere, A. (2024). Is It Safe Enough? An IPA Study of How Couple Therapists Make Sense of Their Decision to Either Stop or Continue with Couple Therapy When Violence Becomes the Issue. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010037

_Chan.jpg)